Most people I know who are fans of some kind or another collected stuff that kept getting more and more popular: Star Trek, Star Wars, comics, certain SF writers. Not so with the stuff I went for: Harlan Ellison’s still a cult writer, the Flashman books never made it big in the States, and the only other person I know who collected vintage National Lampoons was the guy who ran http://www.marksverylarge.com/. (Okay, I did have nearly all of Philip K. Dick’s novels by the time Blade Runner came out. He’s the only success story I can claim to have been into before alla youse posers.)

I first read a Lampoon in 1974: it was the “50th Anniversary Issue,” I was eleven, and I bought it at the Watergate Hotel’s newsstand. I was reading _Mad_ and heard that this “college humor” was something smart kids were into, and talked my parents into buying it. I remember three items from that issue. One was a Gahan Wilson flowchart for horror movies, and us geeky kids dig flowcharts. The second was a comic book that seemed to be about Jesus and Bob Dylan, and since i knew nothing of Dylan at the time it went completely past me. The other was a set of erotic-funny stories by Chris Miller that stirred some novel thoughts in my 11-year-old brain. (I kept hoping my mom wouldn’t look over the back seat and ask me what I was reading. She didn’t.)

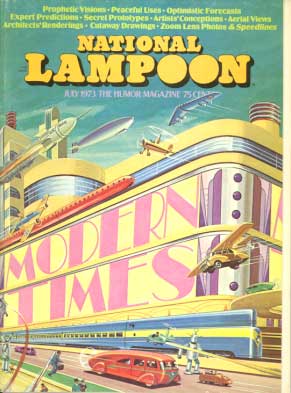

The “Modern Times” issue, July 1973: guest editor Bruce McCall

But the humor went over my head, and I didn’t pick up an issue for another four years. Why’d I start up again? Newsweek ran an article about their Sunday Newspaper Parody, written mainly by two guys named P.J. O’Rourke and John Hughes. It sounded like a really interesting project– and 1978 must’ve been a banner year for newspaper parodies, because that same year a bunch of New York writers (including several former Lampoon writers) created a phony Not the New York Times during one of that paper’s strikes. I snagged the Lampoon’s newspaper parody during a vacation in Wildwood, and the Not the New York Times paper during a trip to NYC when I bought my first movie camera and saw Raul Julia as Dracula on stage. So the Lampoon turns up a lot on family vacations.

This must have been early 1978. Anyway, I started buying the magazine, and suddenly I understood a lot of the humor. After all, a lot of it was coming through NBC every Saturday night, by that time. The first issue I bought was their 100th Anniversary issue, which ran a spread of every cover up to that point. Since my best friend at the time was getting me into comics, I found that older issues could be purchased at places like Creationcon. We even managed to visit the Lampoon’s offices, where they let us into the stockroom to buy back issues: I even recognized the guys working there as models in some of the magazine’s articles.

Even better: I learned that the Lampoon had recently produced a movie coming out soon, Animal House, starring John Belushi.

And because I was the kind of kid who had to learn everything about this, I found an article in a great 1970s magazine called New Times: it was titled “They Only Laughed When it Hurt,” and it told the story of the Lampoon at a time just after its founders had left. I knew who Michael O’Donoghue and Anne Beatts were from their work on SNL, but now I had a sense of the distinct talents of Henry Beard, Brian McConnachie, Bruce McCall, and — especially after _Animal House_– Chris Miller and Doug Kenney.

Michael O’Donoghue

The article also stressed the crucial ingredient of Michael Gross’s art direction. For its first eight issues, the Lampoon looked like an expensive underground comic, with the result of lackluster newsstand sales and poor ad revenues. Gross explained to editor Beard that the magazine’s art direction wasn’t matching the quality of the writing; if they were going to parody postage stamps, he explained, you don’t do a Jack Davis-like goof on the thing. You make them look like real postage stamps. To me, this was a kind of voodoo, where the Lampoon was stealing the powerful mojo of slick commercial design, in order to explode it from within. The article said that, despite the contentiousness of the editors, all agreed “it was Gross who’d delivered the baby.”

The result was a five year run that made the National Lampoon the greatest humor magazine of all time. Henry Beard once explained the editors’ educations as the secret: “We had everything in our heads from bubble gum cards to the Edict of Nantes,” and a piece like Chris Miller’s comic book “G. Gordon Liddy: Agent of C.R.E.E.P.” is a good example of this hyperliterate cross-connection. The magazine could include almost anything: Tony Hendra indulged in some really baroque religious humor with his “Son’O’God” comics (illustrated by Neal Adams), full of humor only a lapsed Catholic could really understand. Sean Kelly could compile a four-page parody of “Finnegans Wake.” And if you thought the Lampoon was all fratboy shit and tit jokes, read Henry Beard’s astonishing “The Law of the Jungle.” It’s a law textbook, about the legal systems of animals, eight full pages in the magazine, and it’s astonishing.

Beard’s brilliance was the governing force of the magazine, but its two most distinctive voices were those of Doug Kenney and Michael O’Donoghue. I can’t improve on Hendra’s description of MO’D in his book/memoir Going To Far, so I’ll summarize. O’Donoghue specialized in profoundly black humor, of a degree and acuteness one rarely experienced outside of Ireland, and almost never in the United States. He cultivated a “Mr. Mike” persona somewhere between Charles Baudelaire and Cardinal Richelieu; refined, dark, and seemingly completely amoral. The prime O’Donoghue piece from the Lampoon may have been his “Vietnamese Baby Book,” a piece where you’re almost forced to laugh wildly at something utterly horrible.

Douglas C. Kenney

Beard came from money, and came to Harvard as a ferociously intelligent man who worked at becoming a humor writer. O’Donoghue was a poet, performance artist, and playwright who lived in bohemian New York City, somehow at home among the underground and Warhol cliques while keeping his imperious, critical distance. But Doug Kenney’s genius was natural, mysterious, and seemingly effortless. He came out of the middle American of Chagrin Falls, Ohio, to become a social chameleon at Harvard, adopting different personas and rapidly insinuating himself into the various social clubs and cliques. But he always had an outsider’s gift of seeing through any social situation he was in, and part of his brilliance was a confused empathy for everyone, even the people he was parodying. (Watch Animal House, and notice how acutely the Omegas are portrayed; that’s Kenney, who knew them inside and out.)

He was also a staggeringly gifted writer. Friends report that he’d ask them to pick a book off a shelf. Kenney would begin to read it aloud… and at some point, he’d stop reading the book, and continue with something else in that writer’s style, seamlessly. While Beard could knuckle down and get his work done, Kenney had to wait for the moment of inspiration to strike. And when it did, he’d turn out brilliantly funny items like “Nancy Reagan’s Guide to Dating Do’s and Don’ts.”

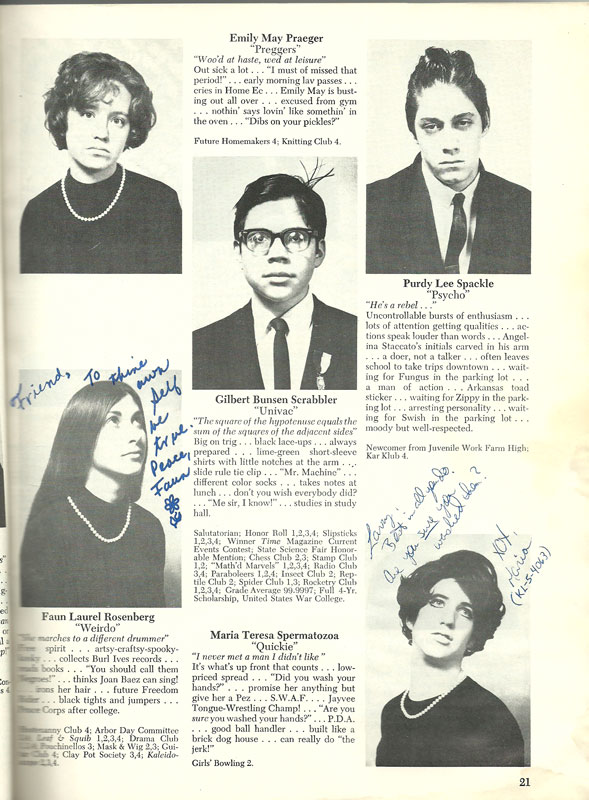

Part of Kenney’s gift was his perfect recall of growing up in postwar America. Most of his pieces are parodies of the sorts of things 1950’s teenagers would have encountered: romance takes like “First Blowjob,” Red-scare stuff like “Commie Plot Comics,” and even a “Classic Comics” adaptation of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. He remembered it all, and every affectionate memory was offset by the later knowledge of how horrible it really was, and both sides came through in Kenney’s writing. And while he gained fame as the co-screenwriter of Animal House (and as “Stork”), his prime achievement may have been the Lampoon’s 1964 High School Yearbook Parody.

The project originated with O’Donoghue in a 1972 issue, but Kenney– assisted by the newcomer P.J. O’Rourke– made it his own. The high school in question is the C. Estes Kefauver High School of Dacron, Ohio, one of thousands of schools built after the war for a generation of kids who were going to get poleaxed by the 1960s. Detailed stories of each kids’ life are packed into the events, photos, and even signatures and messages scrawled in the yearbook. It may seem like a catalog of cliches about high school– the jock, the nerd, the theater kids, the girl who’s into folk music, the girl who sleeps around, the class hoodlum, the one Negro kid in an all-white school– but as Kenney later said, they’d started by assembling high school yearbooks and seeing how these types turned up all the time; it was, Kenney said, “like Nazi social engineering. People became these things.” It’s not hyperbole to say that it’s one of the greatest humor pieces ever written.

The project originated with O’Donoghue in a 1972 issue, but Kenney– assisted by the newcomer P.J. O’Rourke– made it his own. The high school in question is the C. Estes Kefauver High School of Dacron, Ohio, one of thousands of schools built after the war for a generation of kids who were going to get poleaxed by the 1960s. Detailed stories of each kids’ life are packed into the events, photos, and even signatures and messages scrawled in the yearbook. It may seem like a catalog of cliches about high school– the jock, the nerd, the theater kids, the girl who’s into folk music, the girl who sleeps around, the class hoodlum, the one Negro kid in an all-white school– but as Kenney later said, they’d started by assembling high school yearbooks and seeing how these types turned up all the time; it was, Kenney said, “like Nazi social engineering. People became these things.” It’s not hyperbole to say that it’s one of the greatest humor pieces ever written.

I won’t discuss the Lampoon’s live show Lemmings or its wonderful Radio Hour because this is getting too long, and I didn’t even find those things until years later. But these productions gathered together a crew that included Christopher Guest, Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Gilda Radner, and Bill and Brian Doyle-Murray, who were promptly snapped up by Lorne Michaels for SNL. (Michaels insists that the Lampoon wasn’t much of an influence on his show. Which gives you an idea of how Lorne Michaels sees the world.)

So anyway. 1978 may have been the Lampoon‘s climax. O’Donoghue had left by late 1974, and he eventually became the first head writer of Saturday Night Live. Beard was burned out by the workload and the turmoil, but wealthy from his buyout in 1974. The magazine’s publisher, Matty Simmons, had to make money fast to pay Kenney and Beard, so he got a movie into production, and thus Animal House brought Kenney to Hollywood– where he wrote Caddyshack, dove headlong into cocaine, and died by falling off of a cliff in Hawaii.

The editorship passed through Tony Hendra to P.J. O’Rourke by 1978. O’Rourke had come on board as a junior figure, who made himself valuable by assisting O’Donoghue and Kenney in writing filler material and keeping their projects on schedule. Other Lampoon writers tend to disparage him, seeing him as a stalking horse for the profit-hungry publisher, who turned the magazine into Fratboy Monthly. And that’s true; O’Rourke had always felt at odds against what he saw as Harvard-liberal snobbishness, and he decided that an angry white man’s p.o.v. was something really boundary-breaking. And, unlike Beard or Kenney, O’Rourke couldn’t edit other writers without making them sound a bit like himself. So the post-1977 Lampoon could be ugly at times. Josh Karp’s account of the magazine is sympathetic to O’Rourke, who’d wanted to be part of this amazing magazine, and wound up running it… only to find that the people he’d wanted to impress had all gone, leaving him in the role of Mr. Responsible, and an audience that just wanted tits and beer. He did have the good fortune to discover John Hughes, who pretty much co-shouldered the magazine and the newspaper parody, but he left in 1981 to find a better career as one of the few conservative writers worth reading.

While the Lampoon languished, Spy magazine came into being, which was acutely aware of the debt it owed. Every so often, a book would come out about the Lampoon’s golden age: Tony Hendra wrote a memoir, Going Too Far, in 1987, and publisher Matty Simmons did his own a few years later. 1999 saw Dennis Perrin’s biography of Michael O’Donoghue, Mr. Mike, and Josh Karp’s biography of Doug Kenney (A Futile and Stupid Gesture) came out in 2006. 2010 gave us an anthology of high-quality reprints from the magazine, Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead, and next month, Douglas Tirola’s documentary of the same title’s being released to theaters and streaming outlets.

So it looks as though the rest of the world’s caught up to something I knew about forty years ago.

In the meantime, I have a few tubs of vintage National Lampoons– yes, I have the first five years-– to dig out and reread.